If artificial intelligence had never been integrated into the Push Lap Garage project until now, it wasn’t out of excessive caution or a rejection of technology: it was a methodological necessity. Introducing AI into a fuzzy process mostly means automating a mistake. And from day one, Force Feedback has never been treated as a simple comfort setting, but as a complete physical chain: measurable, explainable, and reproducible.

So the real question isn’t whether AI can help, but when it becomes relevant. As long as the link between the simulator’s physics, telemetry, and Direct Drive hardware isn’t locked down, any automation is pointless. With the Ligier JS P325, the building blocks are finally in place to cross that line: a usable MoTeC log, a clear protocol, and robust metrics.

The goal of this episode is simple: show how AI can accelerate an engineering approach that’s already under control—without ever replacing human reasoning.

FFB Calibration — An energy-based approach, not peak-hunting

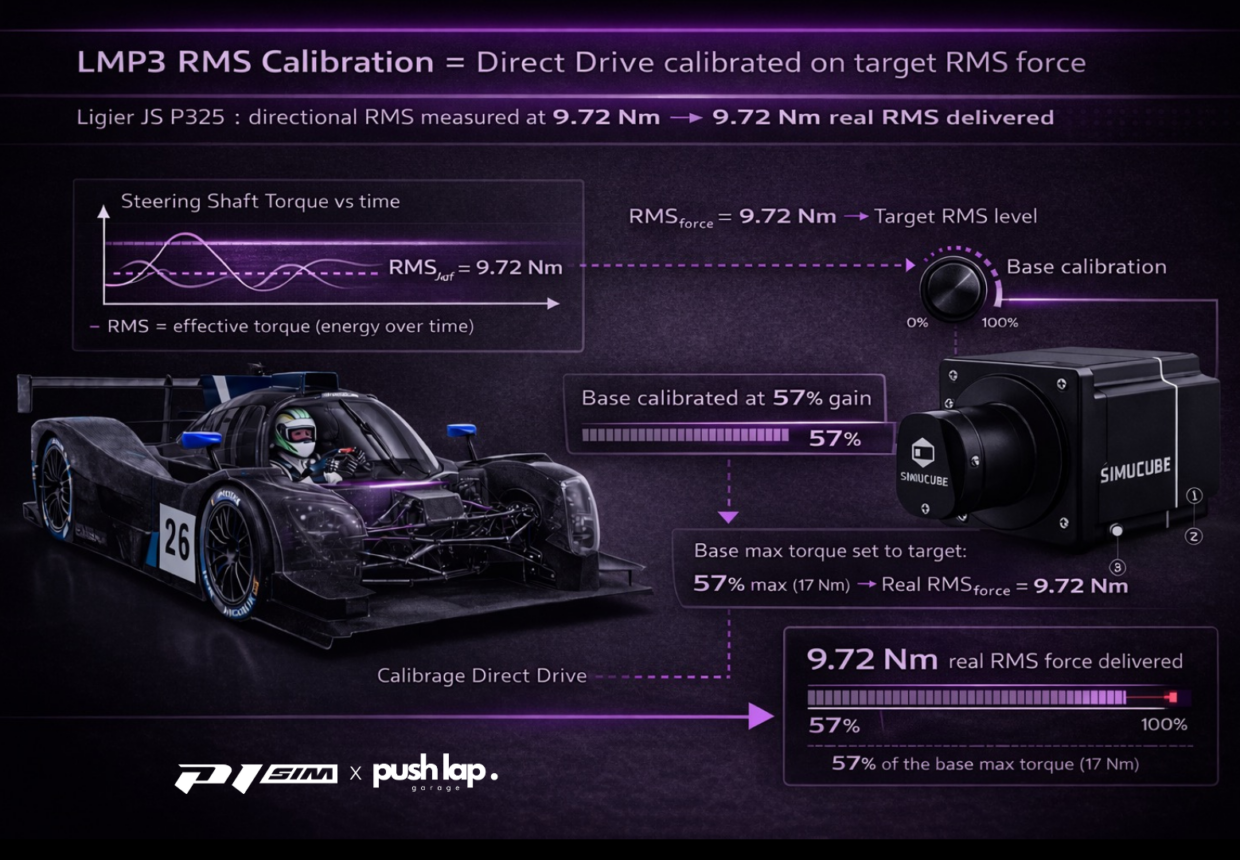

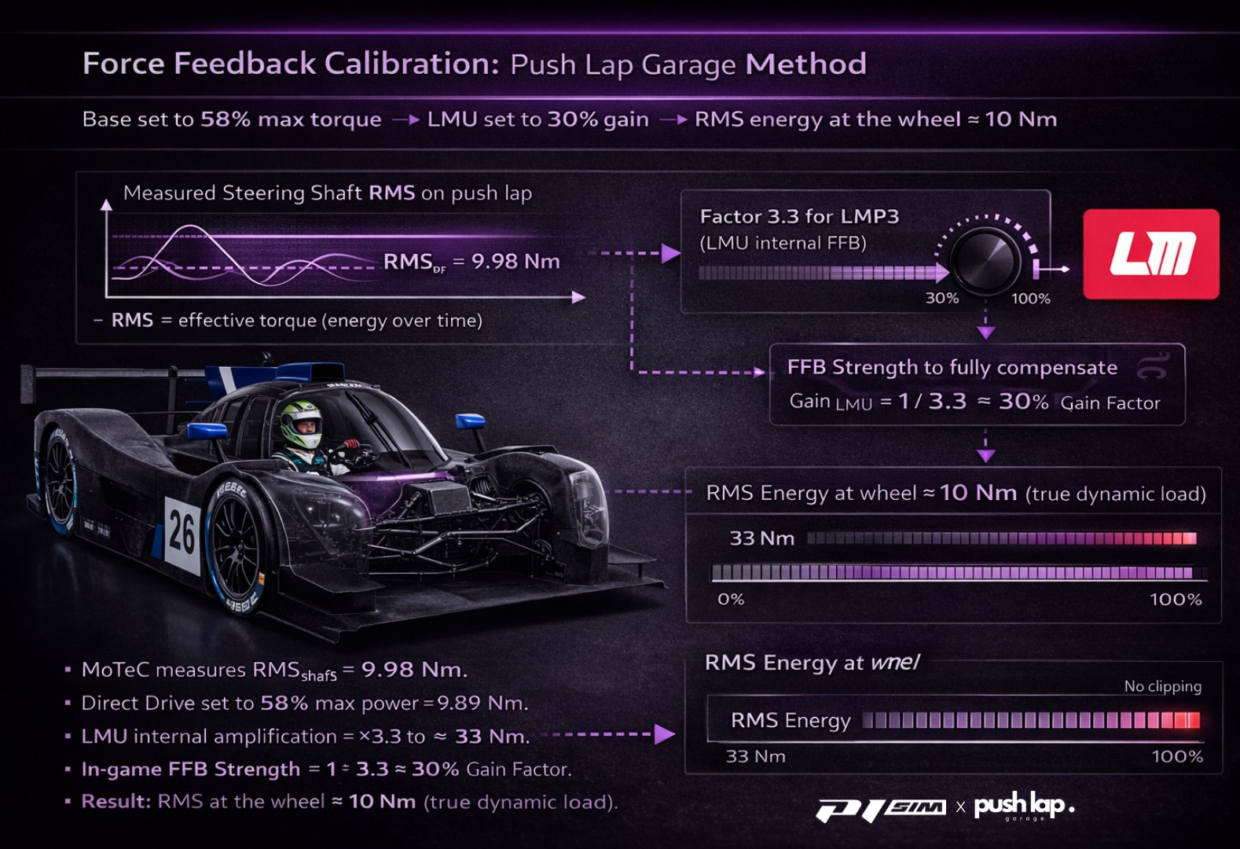

In Le Mans Ultimate, Force Feedback must be understood as a continuous energy system, not a collection of maximum forces. Steering torque is an oscillating signal, constantly changing sign and amplitude: in that context, the physically meaningful quantity for setting the FFB scale is not a peak, but the RMS (Root Mean Square) of steering torque—its effective amplitude over time.

On our MoTeC file (sampled at 100.0 Hz), the on-track analysis yields a shaft RMS of 9.982 N·m, with P99(|T|)=22.470 N·m and max(|T|)=32.520 N·m.

The QA ratios (P99/RMS=2.25, max/RMS=3.26) confirm healthy dynamics: real energy content, with no dominant “glitch.” This RMS value becomes the reference: it sets the scale—not feel, not peaks.

LMP3 and the Ligier JS P325 — A readable laboratory

The LMP3 class is an ideal analysis ground: light car, no assists, simple aero, readable mechanics. It acts like a revealer: every driver input shows up immediately in the data. The Ligier JS P325, as implemented in LMU, becomes a particularly effective platform for applied engineering.

The protocol stays deliberately stripped down: Direct Drive base, a wheel with no “cosmetic” filters, and above all a single objective during the first runs: produce a clean, stable, usable signal—rather than chase lap time.

Rotation, Force Feedback, and acquisition — Building a clean foundation

Steering rotation is the first anchor point in the entire chain. With the Ligier JS P325, the native value is 440°: it’s not negotiable. Changing rotation doesn’t change the “total energy” produced by physics, but it fundamentally reshapes how torque is distributed to the Direct Drive base—therefore impacting readability, stability, and repeatability of your settings.

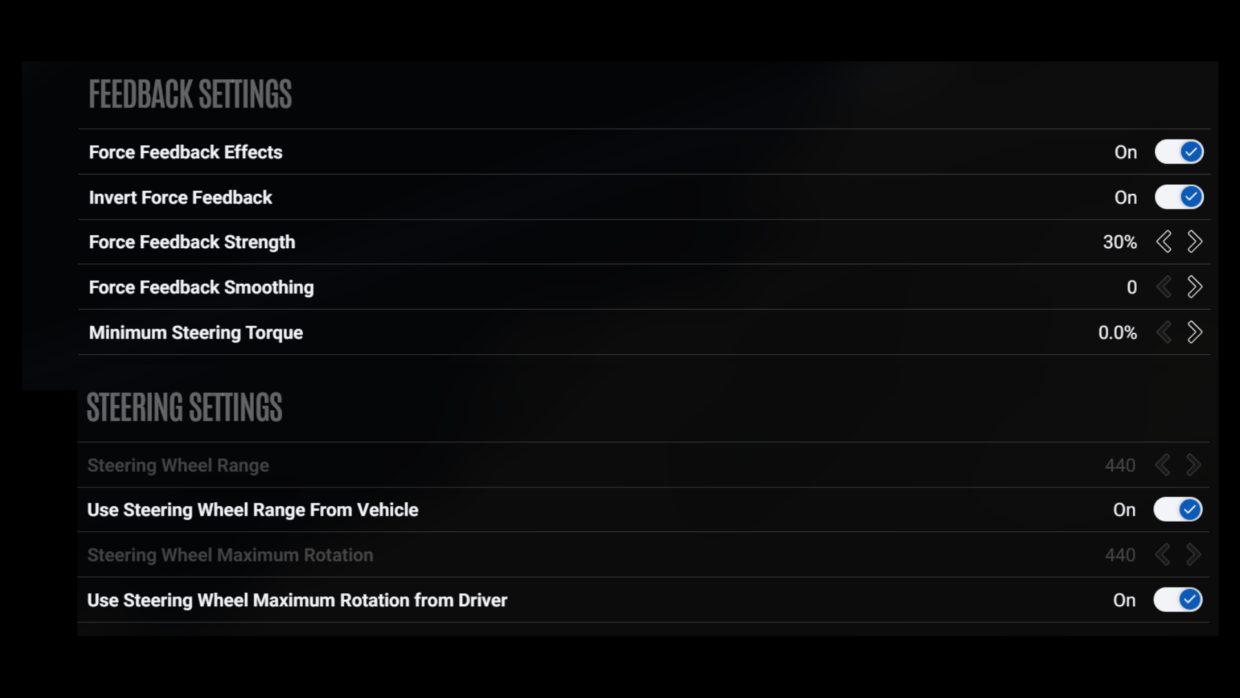

In LMU, rotation can stay on automatic on the sim side, but the method requires a fixed point on the base side: 440° in SimuCube. Then, during acquisition, base power can be voluntarily capped (e.g., 30%) to avoid unnecessary saturation and drive more relaxed. Same logic in-game: a temporarily fixed FFB (e.g., 30) helps smooth driving and therefore a cleaner MoTeC read. The goal of this first session is not performance: it’s statistical data quality.

This is where the P1 SIM Eau Rouge wheel becomes a full engineering tool. Thanks to its “key” button, we can manually trigger MoTeC telemetry recording at the exact moment the information becomes relevant: tires up to temp, clear track, stabilized pace, “representative” braking. We no longer suffer a continuous log mixing out-laps, traffic, or pit return phases: we target acquisition, and drastically reduce statistical pollution.

That precision changes what the CSV file is: it becomes an intentional capture of physics, not a noisy history. And that’s the backbone of this article—because recording is triggered “at the right time,” RMS metrics and quantiles describe what we actually want to measure (real transmitted energy, real pedal range used), not a compromise between useful and useless periods. A few clean laps are enough to produce a usable and above all reproducible file.

RMS, percentiles, and AI — From CSV to a decision

Once imported into MoTeC, the data collapses into robust indicators: RMS for energy, percentiles (P99) for QA, and segmentation to keep only what matters. Then the CSV becomes the hinge: the shared baseline between telemetry, human reasoning, and the AI tool.

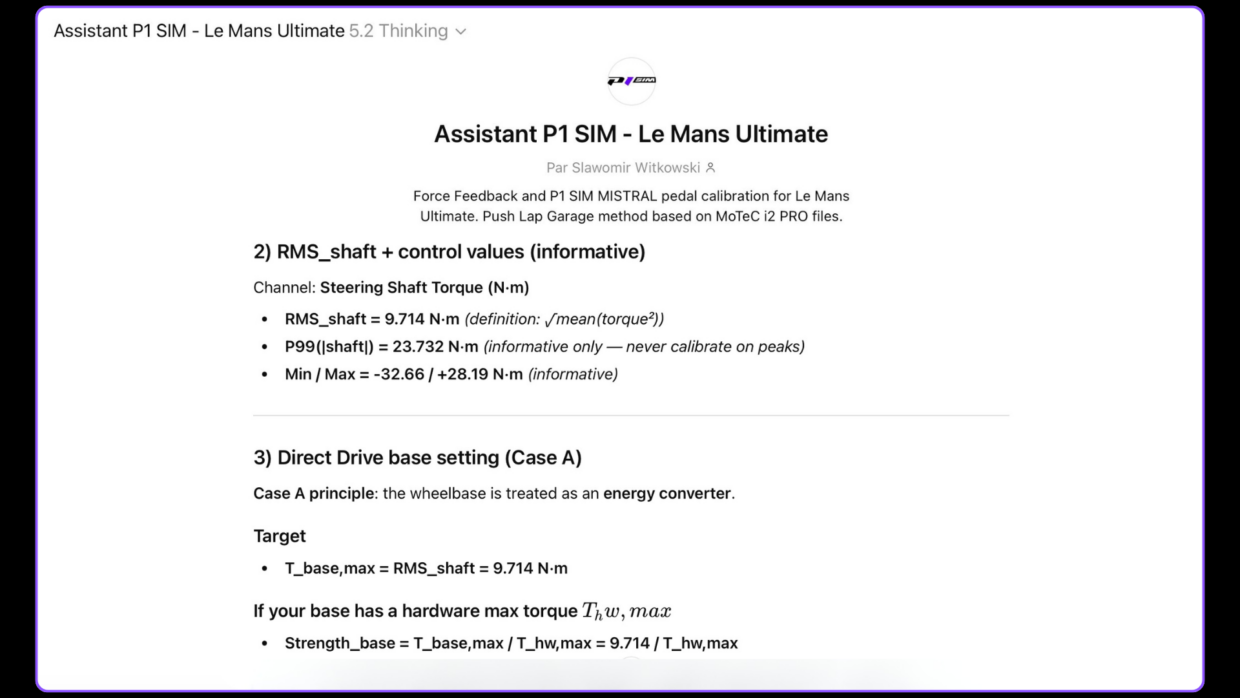

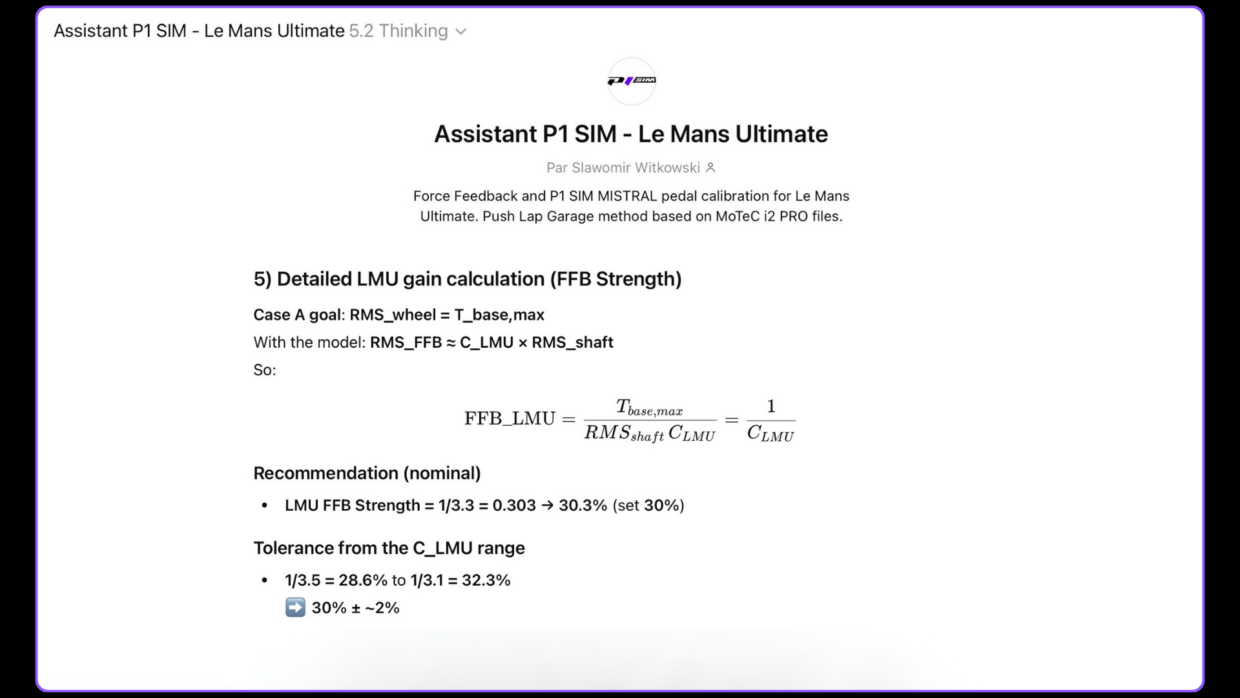

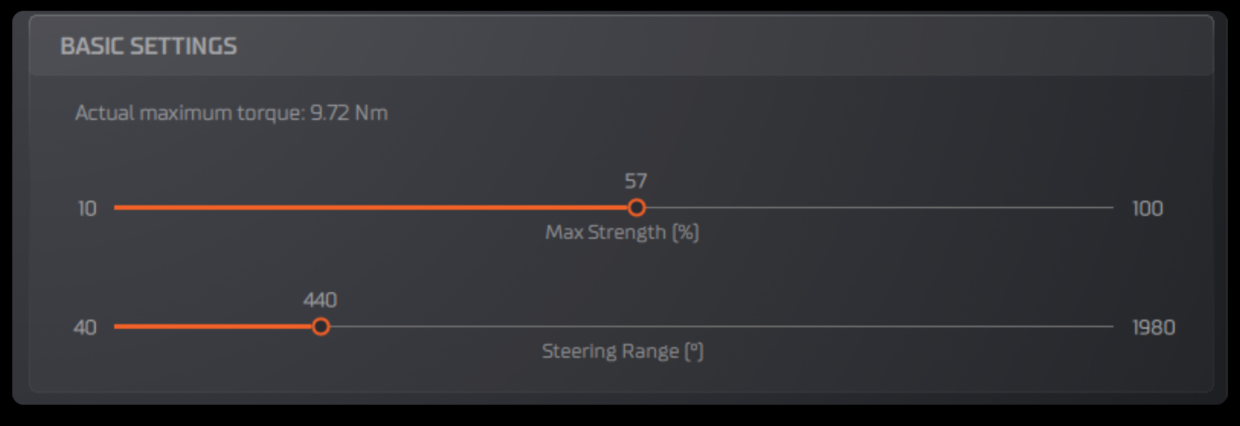

At this stage, the GPT doesn’t invent anything: it applies defined formulas, mechanical constraints, and explicit segmentation rules. In our case, the target is clear: RMS_shaft = 9.72 N·m.

On a SimuCube 2 Sport (17 N·m max), that means setting base strength to 9.72 / 17 = 57% so the maximum deliverable torque matches the measured energy reference. Once that point is fixed, the base no longer “decides”: it executes.

From measured RMS to felt FFB — How LMU transforms energy

Once the base is calibrated on RMS, LMU still needs to be set. For an LMP3, the internal model amplifies the signal energy through a class factor: C_LMU ≈ 3.3 (typical range [3.1 ; 3.5]). The rule becomes mechanical: FFB_LMU = 1 / C_LMU.

Concretely: 1/3.3 = 30.3% (range 28.6% → 32.3%). Margin verification is immediate: in our log, FFB Output stays far from saturation (RMS 16.913%, P99 39.007%, max 59.568%).

So: no prolonged clipping, no “game compressing the signal,” and still headroom for the highest-load zones.

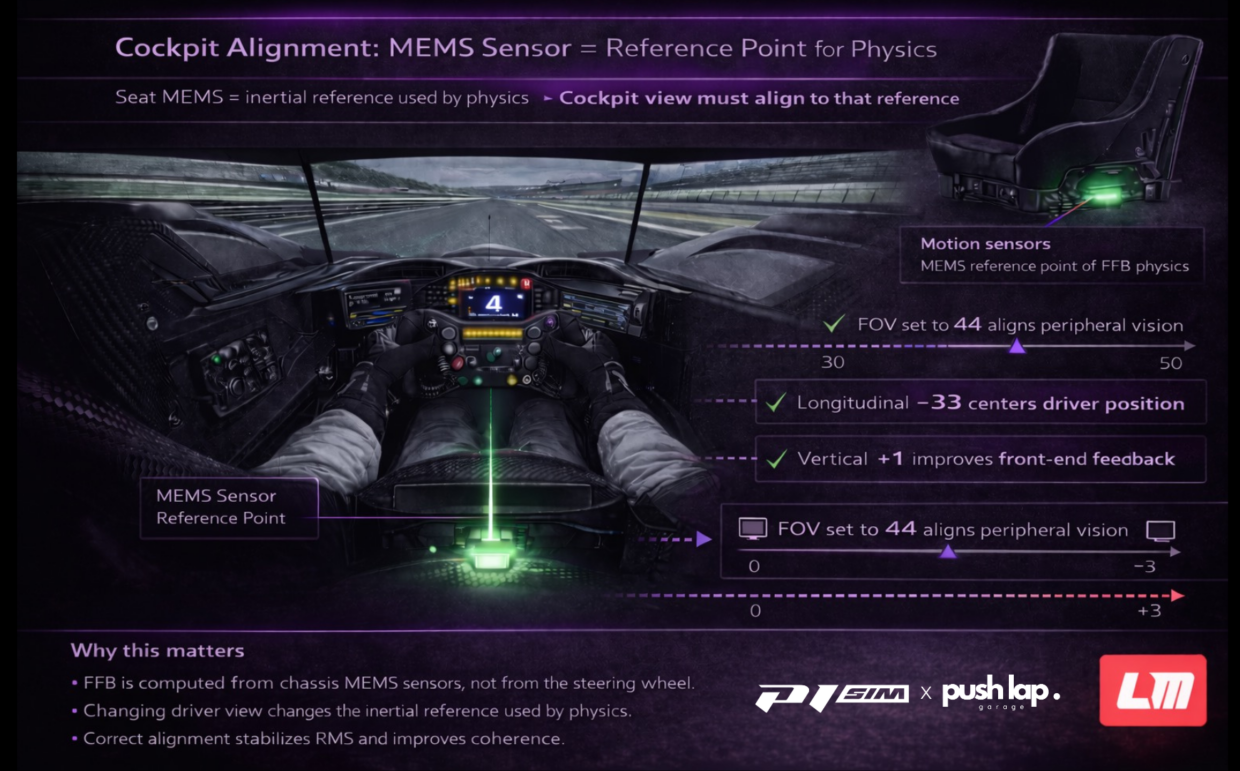

MEMS, FOV, and driver position — Aligning the inertial reference

One often neglected point deserves real attention: Force Feedback isn’t the result of a physics calculation based on the chassis inertial frame. Changing the virtual driver position therefore shifts your perceptual reference relative to the calculation reference. And when you’re chasing coherence, that offset eventually shows up in signal stability.

The first element to determine is FOV, which depends on your resolution. In our specific case (10320×1440), FFB starts becoming interesting from 46, to validate 44.

Then adjustment progresses along the other two axes: longitudinal and vertical. By stepping the longitudinal position backward, a clear change appears around -33: steering becomes smoother, more coherent, more stable under load.

Vertical adjustment refines it further: at +1, the front end gains readability and steering load becomes more homogeneous. Here, validation doesn’t rely on feel alone: RMS behavior stabilizes—sign of a more coherent alignment between physics and perception.

SILVERSTONE: a track that “loads” braking

At the Silverstone, braking is particularly “loaded” because the track combines heavy braking zones, loaded turn-ins, and load variations (crests/compressions) that make pedal feel less consistent than elsewhere.

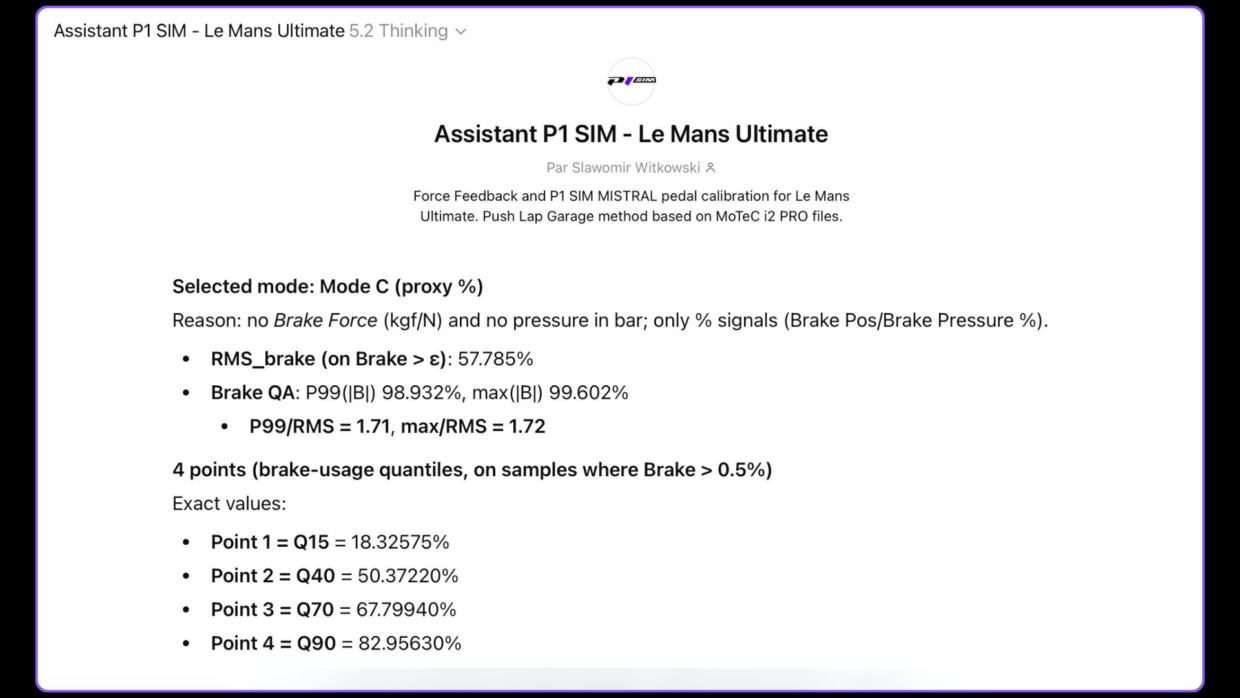

To objectify what’s really happening, we rely on a clean MoTeC log: 107.49 s of data at 100.0 Hz (dt ≈ 0.0100 s), then we strictly segment the relevant phases.

We keep only on-track running (Ground Speed > 5 km/h, In Pits=0), and isolate effective braking via Brake Pos Filtered > 0.5%: that represents 2,500 samples, i.e. 25.00 s of “active” braking within the analyzed window.

This method avoids conclusions drawn from micro-taps or non-representative phases, and keeps focus on energy actually injected through the brake.

MoTeC — Numbers that turn sensation into a setting

Once segmentation is done, the numbers immediately describe Silverstone braking intensity: on braking samples only, usage is very sustained with RMS_brake = 57.785%.

Quantiles confirm you spend a lot of time in the upper pedal zones:

And the end of travel is regularly used: P99 = 98.932% for max = 99.602%, with ratios P99/RMS = 1.71 and max/RMS = 1.72 (strong usage, but no abnormal isolated spikes).

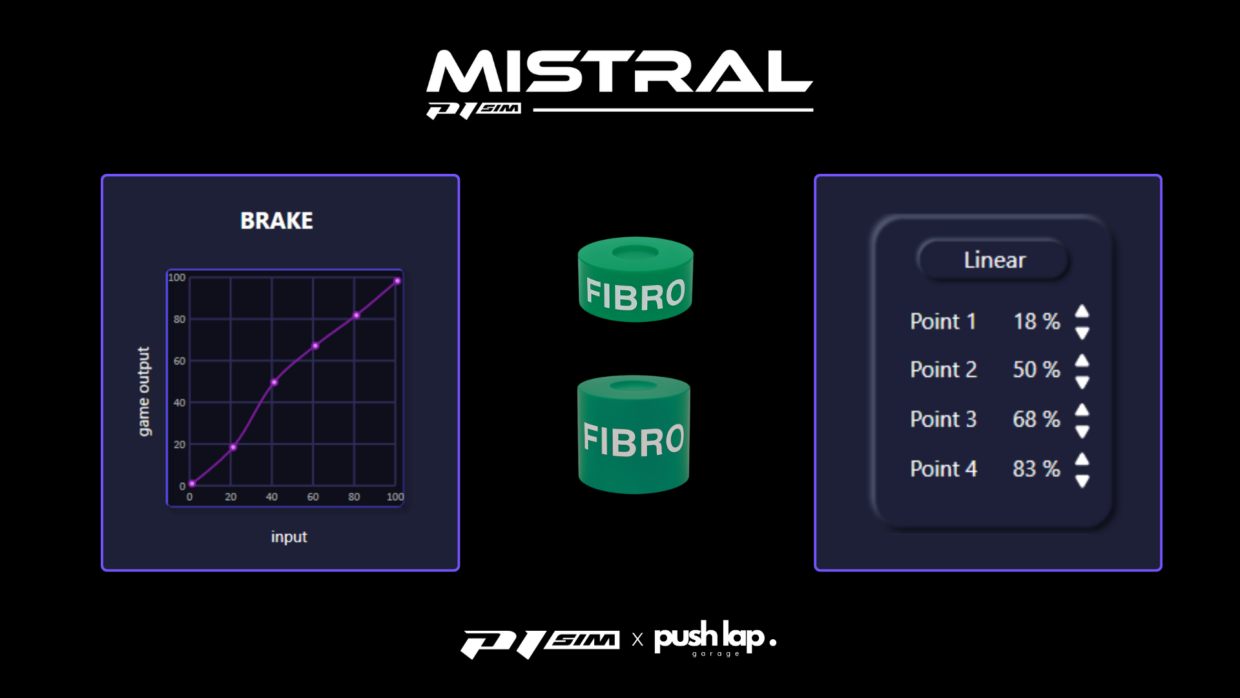

That clarity lets us directly calibrate the P1 SIM 4-point brake curve from real usage: 18.3% / 50.4% / 67.8% / 83.0%(Q15/Q40/Q70/Q90), which stabilizes the progression between initial bite, transition, load, and saturation—a decisive advantage on a track as “undulating” as Silverstone.

Conclusion — AI as an accelerator, never as the driver

This episode marks an important step in the evolution of Push Lap Garage. AI is not presented as a miracle solution, but as a way to industrialize reasoning. Without clean data, coherent hardware, and a rigorous method, it’s useless. With the right tools, it becomes brutally effective.

The Ligier JS P325 allowed us to establish a clear, reproducible, measurable framework: energy-based RMS calibration, margin control via percentiles, and turning a MoTeC CSV into concrete decisions—no disguised intuition, no “by-feel” settings. And if this chapter works, it’s because acquisition itself became methodical: targeted triggering via the P1 SIM Eau Rouge “key” button, strict segmentation, then RMS and quantile computations on clean data.

Finally, this chapter opens another trajectory: the P1 SIM GPT. Until now developed as an internal tool to validate, accelerate, and secure analysis, it will evolve, grow richer, and become methodologically stricter before being released publicly. The objective remains the same: AI is useful only when it is anchored to a method and data—never when it fills gaps with assumptions.

Bonus

Leave a Comment