The previous episode, dedicated to the Ligier JS P325, marked an important milestone in the evolution of the Push Lap Garage project. For the first time since this methodology began, MoTeC data analysis no longer relied solely on the driver’s experience and manual curve interpretation. Instead, it was supported by a tool capable of structuring, verifying, and challenging hypotheses: a specialized GPT designed to automatically parse telemetry files and extract the most relevant physical indicators.

GPT Assistant

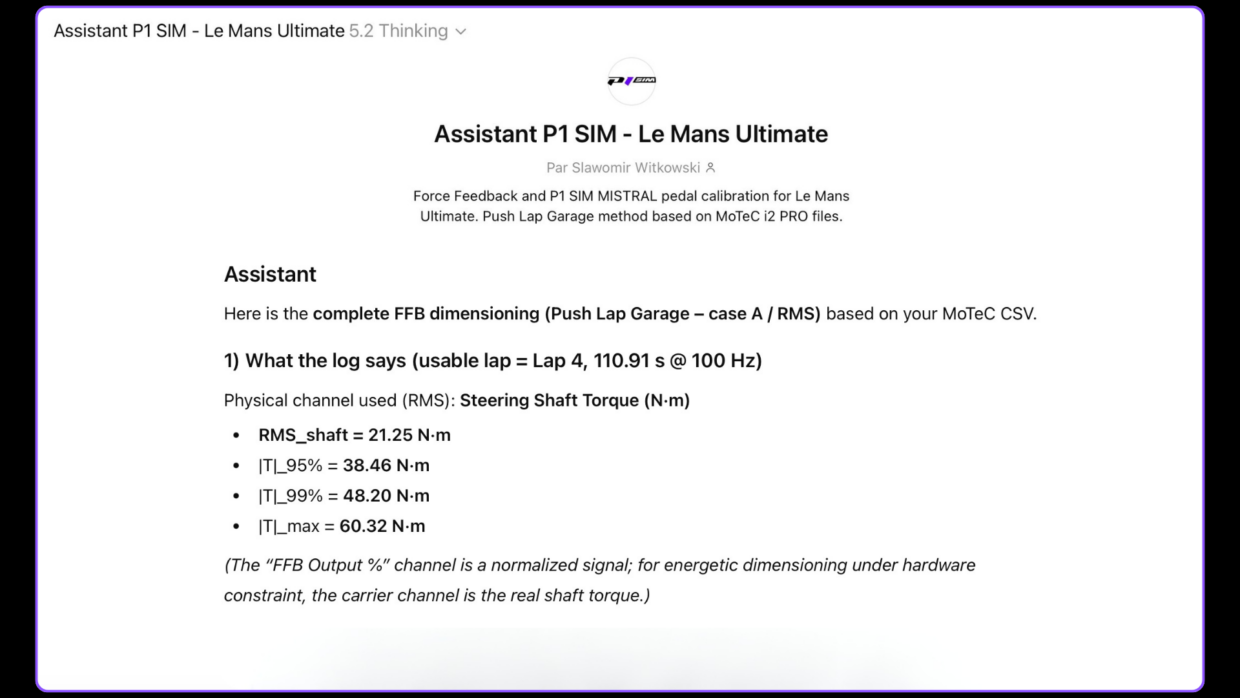

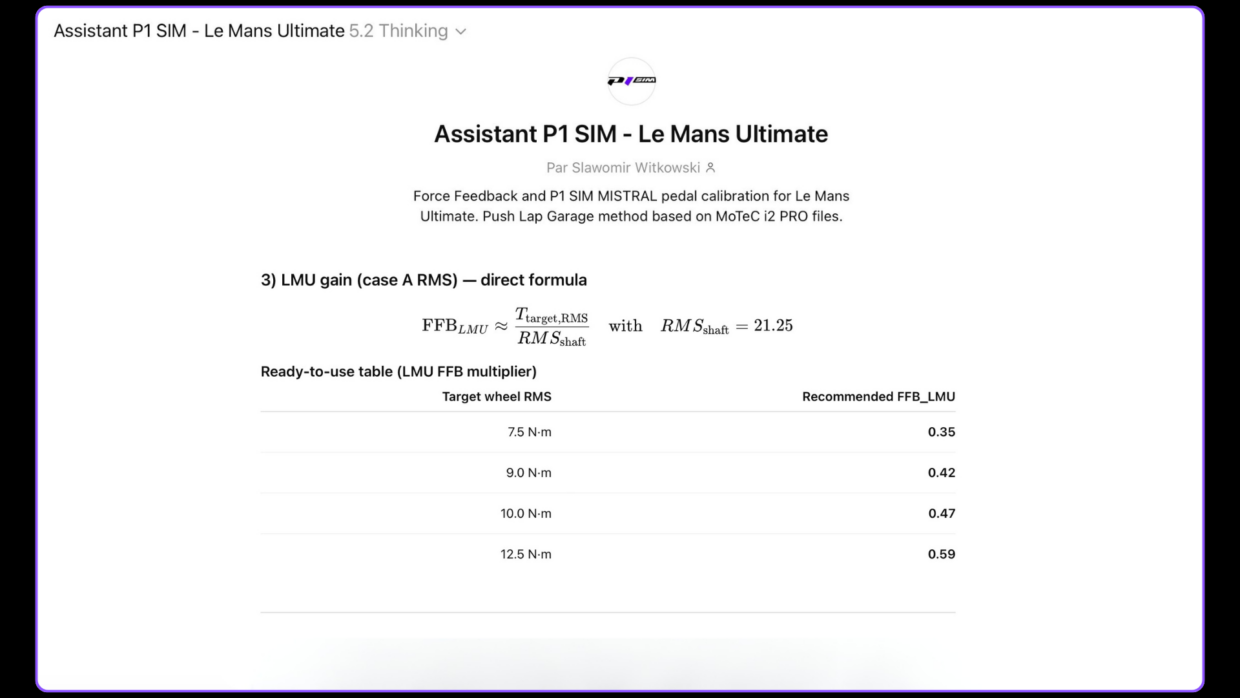

Concretely, this assistant was anything but a gimmick. It was able to read raw channels, isolate steering shaft torque, calculate RMS, P95, and P99 values, and then propose a theoretical Force Feedback sizing based on an explicit energy relationship.

At Monza, with the LMP3, this approach delivered particularly convincing results. The recommended gain did not stem from intuition, but from calculations grounded in measured loads. On track, the steering wheel “spoke,” information flowed coherently, and sensations closely matched the data. For the first time, methodology, measurement, and driving truly converged.

At this stage, it was tempting to consider this validation as an endpoint. The method appeared robust, reproducible, and transferable. The protocol was in place, the tool worked, and results were consistent. Nothing suggested an imminent major reassessment.

But simulation, like real-world competition, never forgives premature certainties.

On Track with the LMP2

When I took the wheel of the ORECA 07 LMP2 at Silverstone, the objective was precisely to test this transferability. Same analytical environment, same GPT, same recording protocol, same locked geometric parameters. Everything was designed to replicate the LMP3 conditions—except for one fundamental factor: the car itself, heavier, more powerful, and far more demanding in energy terms.

The first laps quickly confirmed that something was not working as expected. Despite applying the same method as with the LMP3, the steering wheel offered significant—sometimes excessive—resistance. An overly abrupt torque buildup and sustained load phases resulted in an almost constant force, difficult to modulate.

Very quickly, a more concerning phenomenon emerged: despite this intensity, directional information faded. Fine load variations—the ones that allow anticipation of grip limits—were no longer perceptible. The steering became heavy, saturated, and paradoxically mute, contradicting the excellent results previously obtained.

At this point, two approaches were possible:

The first consisted of empirical correction: slightly reducing gain, adjusting the base, testing different combinations until an acceptable compromise was found. This approach can work in the short term, but it essentially relies on the driver adapting to a poorly calibrated system.

The second, more demanding, involved suspending any immediate compensation and returning to fundamental analysis: revisiting raw files, verifying assumptions, questioning models, and confronting theory with measurements.

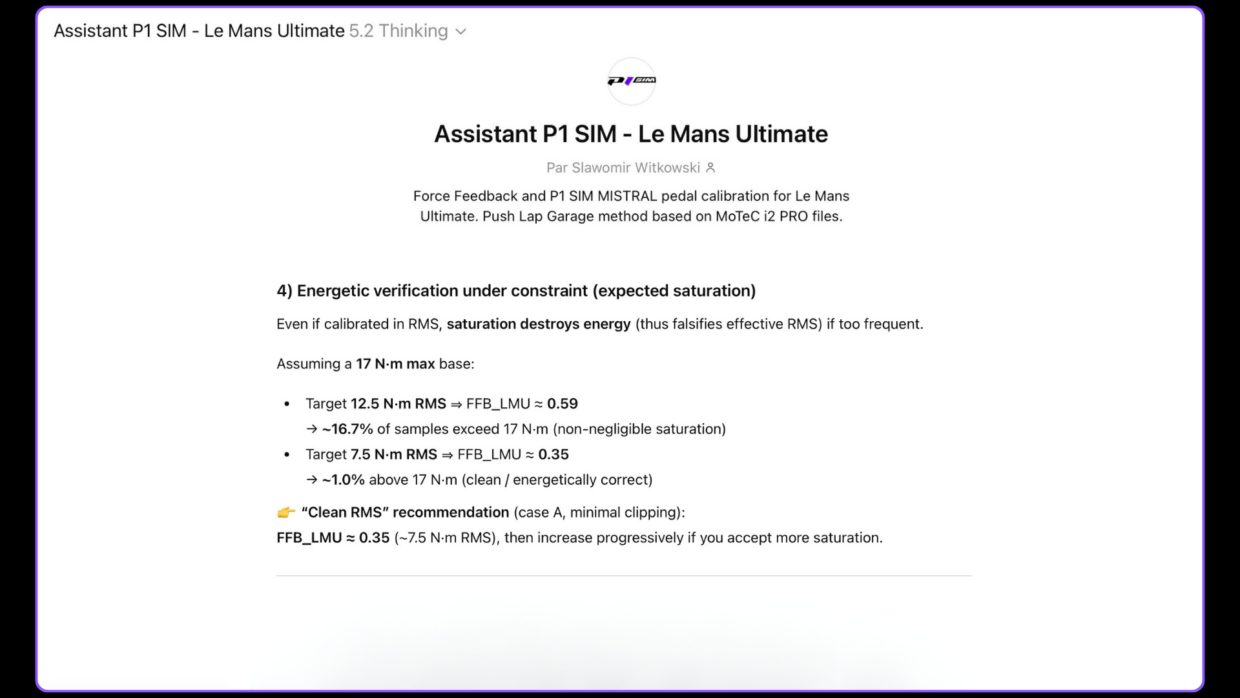

By confronting my results with the studies of Milliken, Pacejka, and Gillespie, one conclusion became evident: the method had to be revised. The amplitude of LMU physics had to be adapted to the capabilities of my SimuCube 2 Sport.

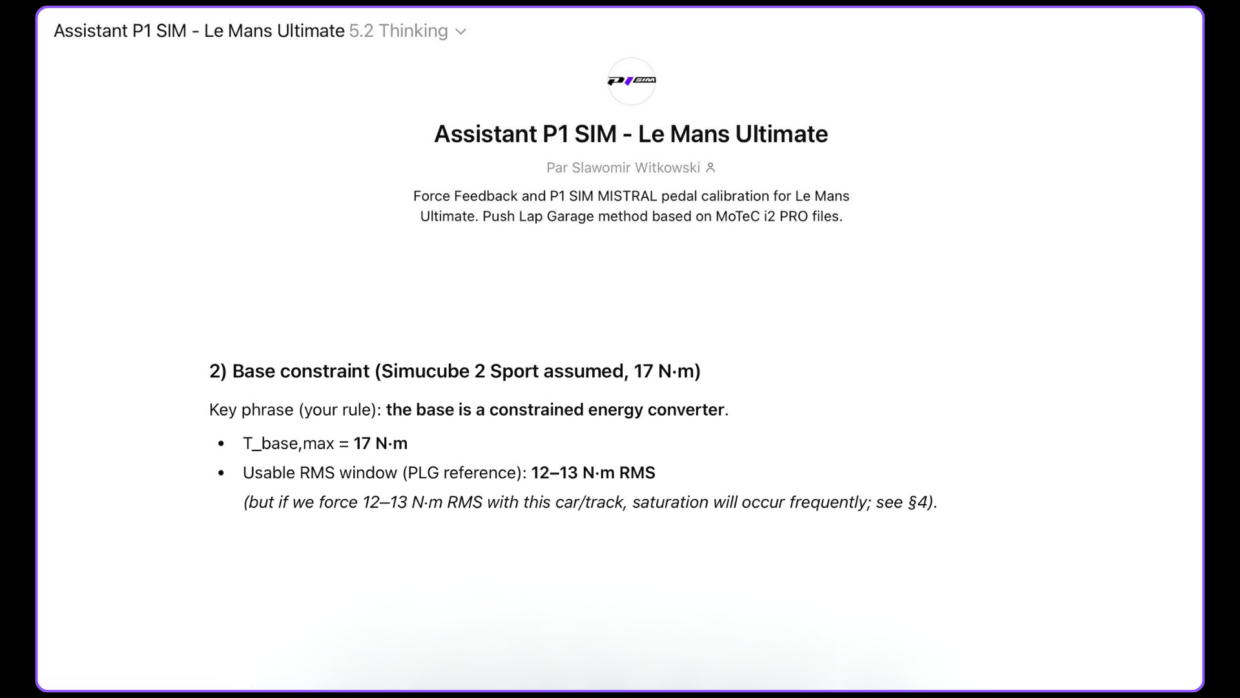

Returning to MoTeC analysis, another realization emerged. On an LMP2 operated on a base limited to 17 N·m, using an intermediate coefficient—no matter how well calibrated on another car—mechanically introduces energy distortion. The method validated on the LMP3 cannot be transferred as-is. Torque conversion must be reconsidered, not as a multiplier, but as an energy flow.

By adapting LMU FFB amplitude to the capabilities of my Direct Drive, I gradually regained something coherent. Determining the true limit of a wheelbase is extremely difficult, and there is often a tendency to artificially constrain the simulation. Yet, adopting the right settings undeniably revives fine details and allows the qualities of a title like Le Mans Ultimate to fully emerge.

Next came cockpit positioning. I often emphasize this aspect, but it is crucial to Force Feedback perception.

As usual, FOV (44 in my case) and screen resolution must be taken into account. This work may seem tedious, but it is essential for accessing the fine details so eagerly sought.

With my triple 34-inch screens at a resolution of 10,320 × 1,440, I manage to reproduce a position very close to reality. A subtle balance between FOV and ideal seating position, perfectly aligned with physical data.

Then comes braking—just as fascinating.

Instrumented Braking: From Raw Pressure to Exploitable Information

A correctly calibrated steering system is not enough to guarantee consistent driving if the deceleration phase remains approximate. In a modern prototype—especially in endurance—braking is an information system in its own right. It governs entry stability, load transfer management, and the ability to reproduce pace over time. It cannot therefore be treated as a simple comfort setting.

As with steering, braking analysis starts by securing the measurement chain. Data is collected at Silverstone using the P1 SIM Mistral pedal set, under the same synchronized trigger protocol used for Force Feedback. Each deceleration phase is directly correlated to a precise on-track situation, free from pollution by unusable laps or off-pace sequences.

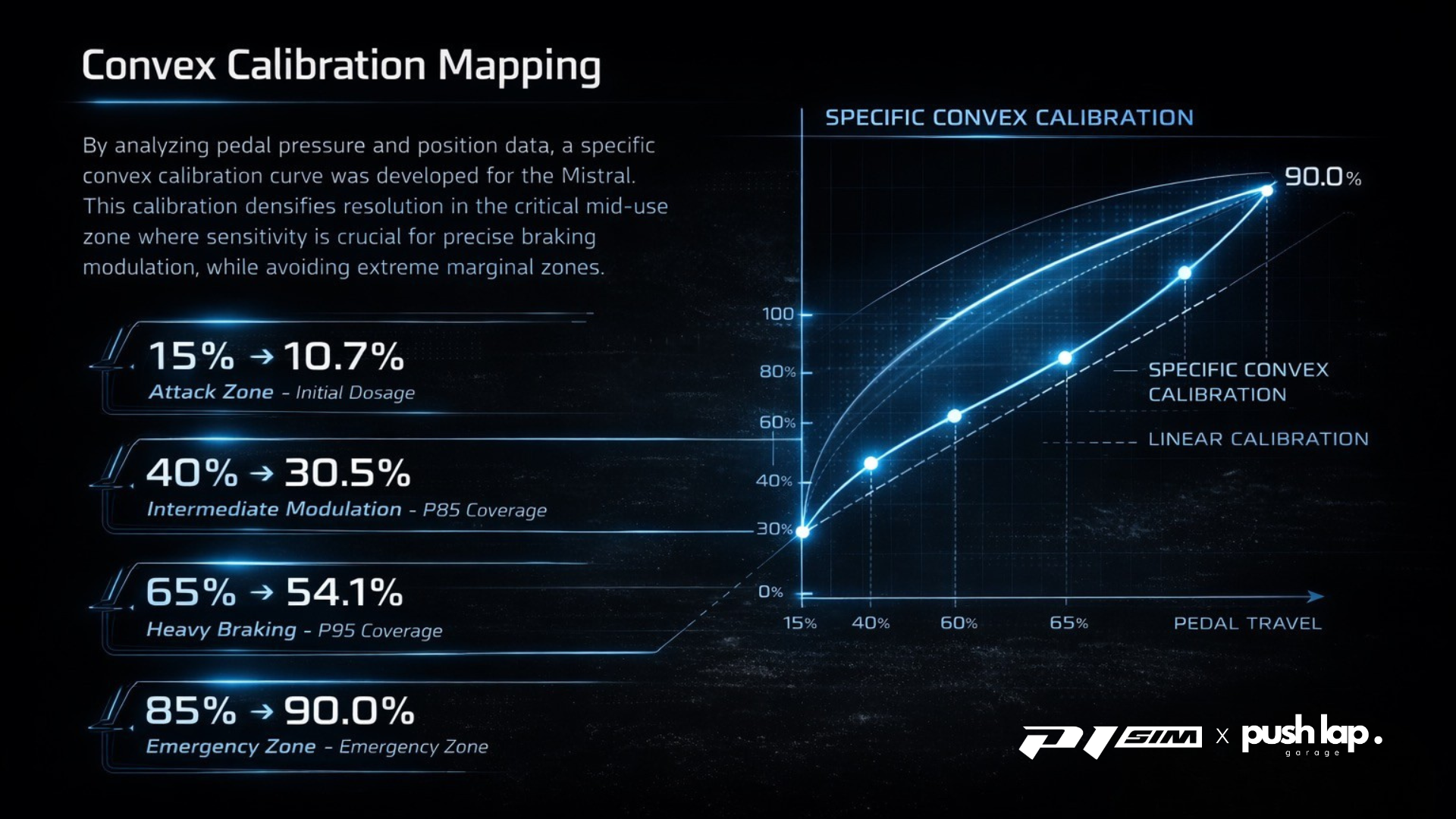

Extracting pressure and pedal position channels in MoTeC quickly reveals a strongly asymmetric distribution. Over the analyzed stint, usage RMS sits at 20.40%, while P95 reaches 51.06%, with an absolute maximum measured at 86.41%. These values reflect a well-known track engineering reality: most driving happens inside a relatively narrow band, while extreme solicitations remain marginal.

Concretely, more than 80% of useful braking phases fall between roughly 30% and 55% of effective travel. That is where entry precision, stability, and rotation-phase modulation are decided. Any mapping that does not prioritize that range mechanically condemns fine control.

A strictly linear curve distributes resolution evenly across the full travel. It therefore grants as much sensitivity to rarely used zones as to critical zones. Functionally, that is counterproductive—it dilutes information exactly where the driver needs it most.

Based on this distribution, a dedicated convex calibration curve is built for the Mistral to densify resolution in the dominant usage band. The retained reference points are:

This mapping profoundly changes the relationship between physical effort and software response. It allows the Mistral’s mechanical finesse to be fully exploited without sacrificing maximum capability. Braking becomes progressive, readable, and repeatable, even under high constraint.

The question of maximum admissible force is the second part of the problem. The Mistral can withstand up to 200 kg, but such a value has no functional interest in real endurance conditions. Tests and analyses converge toward a target around 78 kg—corresponding to the maximum sustainable effort without degrading precision over a prolonged stint.

This threshold is deliberately positioned relative to 90% of the in-game signal. It preserves functional margin, avoids permanent use of the mechanical stop, and maintains sensitivity in the useful range. The driver no longer “pushes” to hit a number, but works within a biomechanically coherent operating band.

This approach aligns three dimensions often treated separately: pedal mechanical capacity, driver physiology, and digital braking modeling. When these three levels match, deceleration stops being an exercise in constraint and becomes a precise positioning tool.

Conclusion: From Empiricism to Physical Coherence

The work carried out around the ORECA 07 LMP2 at Silverstone goes far beyond the search for a single fast setting. Above all, it illustrates Push Lap Garage’s gradual transition toward a fully instrumented approach grounded in systematic confrontation between theory, measurement, and on-track validation. Through this process, Force Feedback stops being a comfort parameter and returns to what it fundamentally is: a mechanical information channel.

By mobilizing the work of Milliken, Pacejka, and Gillespie, then confronting it with MoTeC-derived data, it becomes possible to exit empirical tuning for good. Settings no longer rest on impressions, but on statistical distributions, hardware constraints, and explicit energy relationships. Every adopted value can be traced to a measurement, a physical ceiling, and an identifiable model.

Direct energy conversion—embodied here by 36% in Le Mans Ultimate and 45% on the base—is the outcome of that reasoning. It aims neither to artificially soften the steering nor to maximize perceived force, but to restore a functional hierarchy between average load, transient phenomena, and saturation. The wheel doesn’t merely become more pleasant; it becomes readable, structured, and usable again.

The same logic structures the braking approach. By relying on RMS and P95 indicators, Mistral calibration prioritizes real usage rather than extreme edge cases. The convex curve and the 78 kg cap reflect the intent to align biomechanics, mechanics, and digital modeling within the same coherent reference frame. Here again, the goal is not to make driving harder, but more informative.

In this system, the GPT has a precise role. It replaces neither human analysis nor driving experience. It acts as a methodological accelerator—processing large volumes of data quickly, detecting inconsistencies, and proposing quantitatively defensible hypotheses. It is this constant interaction between automation and on-track validation that sustains high rigor without falling for the illusion of automatic optimization.

Leave a Comment